Hall of Famer Bill Russell, 88, the linchpin of the Boston Celtics dynasty that won eight straight titles and 11 overall during the 1960s, died on Sunday. The statement did not give a cause of death, but Russell had not been well enough to present the NBA Finals MVP trophy (bearing his name) in June because of a long illness.

A champion on the court and a champion for civil rights, Russell's life was defined by perseverance and humility, hardened during an era of social, cultural and political upheaval; the first Celtics dynasty he was a member of was a pioneer in race relations. Russell became an advocate of sports and activism, with his willingness to speak out and participate in the struggle for equality as the Celtics dominance of the NBA coincided with the Civil Rights Movement of the 60s.

When Russell was elected to the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1975, Red Auerbach, who planned his arrival as a Celtic and coached him on nine championship teams, called him “the single most devastating force in the history of the game.”

Today, he remains the sport’s most prolific winner and a revolutionary who won with defense and rebounding while leaving the scoring to others.

“If you can take something to levels that very few other people can reach,” he told Sports Illustrated in 1999, “then what you’re doing becomes art.”

Adding the vertical to the horizontal

“My first varsity game (at USF), we played at Cal Berkeley, '' Russell said in a 2013 interview. “Their center was a preseason All-American. The game starts and the first five shots he took, I blocked. And nobody in the building had seen anything like that. So they called a timeout to discuss what I was doing. We get in our huddle, and my coach says, ‘You can’t play defense like that.’ He showed me on the sidelines how he wanted me to play defense. I go back out and I try it, and the guy (scores on) layups three times in a row. And I said, this does not make sense. So I went back to playing the way I knew how.”

The results were astonishing, subsequently Bill Russell led San Francisco to NCAA titles in 1955 and 1956. In 1956 he also led the US to an Olympic gold medal. Soon after, he would go on to become the facilitator for the greatest NBA championship run in history. He led the Celtics to eight consecutive NBA titles from 1959 to 1966, far eclipsing the Yankees’ five straight World Series victories (1949 to 1953) and the Montreal Canadiens’ five consecutive Stanley Cup championships (1956 to 1960).

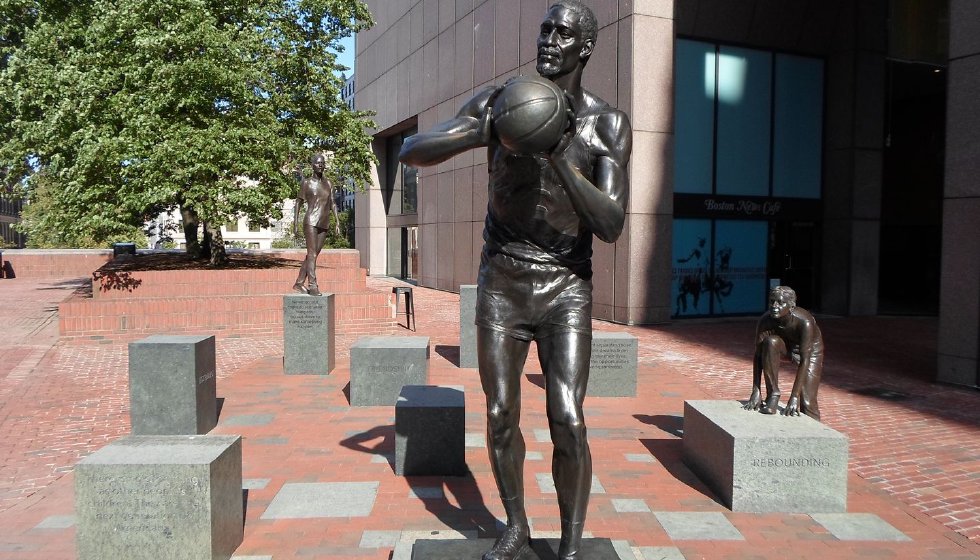

With a focus on winning in an NBA with fewer than 10 teams, Russell changed the game as a remarkable shot-blocker who revolutionized NBA defensive concepts. No good defensive players ever left his feet on defense prior to Russell. To have the imagination to extend his defensive acumen vertically, Bill Russell redefined what it meant to be a defensive center in the NBA. During his career Russell pulled down 21,620 rebounds - an average of 22.5 per game - with a single-game high of 51 against the Syracuse Nationals in 1960.

With blocked shots unrecorded until the 1973-74 season we unfortunately will never, statistically at least, know the full scale of his ability to alter games. Nevertheless in Boston he transformed the Celtics into a fast breaking, transitioning quickly from defense to offense and ultimately into an unrivaled dynasty. His 13 years with the franchise brought 11 titles, while he won five MVPs and earned 12 All-Star appearances. In many ways, Russell was one of the foundations that established the NBA as we know it today.

Former Celtics coach and president Red Auerbach said it best, “Russell single-handedly revolutionized this game simply because he made defense so important.”

When Chamberlain and Russell collided

Wilt Chamberlain entered the NBA during the 1959-60 season and began an epic 10-year rivalry that would become the blueprint for the direction the sport was headed. Russell was agile, Chamberlain the epitome of power. Wilt may have statistically outshone Russell but in terms of winning, counting the regular season and the playoffs, Russell’s Celtics were 86-57 against Chamberlain’s teams for a .600 winning percentage. Every great champion needs the challenge of a rival, no more so than in the physical 5-on-5 of NBA basketball.

“I was the villain because I was so much bigger and stronger than anyone else out there,” Chamberlain told the Boston Herald in 1995. “People tend not to root for Goliath, and Bill back then was a jovial guy and he really had a great laugh. Plus, he played on the greatest team ever.”

“My team was losing and his was winning, so it would be natural that I would be jealous. Not true. I’m more than happy with the way things turned out. He was overall by far the best, and that only helped bring out the best in me.”

Those who had watched Russell and Chamberlain play individually before had never seen either man seriously challenged. The Big Collision would push both athletes to greater heights, to demand more of themselves as finally, they had found an opponent worthy of their own talent. The matchups between Bill and Wilt was a new beginning of basketball, becoming one of basketball’s greatest rivalries long before Magic and Bird would come to define the Lakers & Celtics rivalry in the 1980s.

Civil Rights Icon

Success, though, couldn’t hide a strained relationship with the city where he played. A simple characteristic of Bill Russell’s life and times that can’t be separated from his accomplishments: he was born a black man in Louisiana, United States in 1934.

When he barnstormed with other NBA players during the summer to make some extra cash, hotel owners denied rooms to Russell and his Black teammates. One day, as Russell and his family were out of town on a family trip, burglars broke into Russell’s Boston-area home, smashed his trophies, defected on his bed and spray-painted the N-word on the walls. The incident would have a profound impact on his relationship with the city of Boston.

“I played for the Celtics, period,” Russell once told his daughter Karen. “I did not play for Boston. I was able to separate the Celtics institution from the city and the fans.”

Russell could not easily remove the memories of Boston during his playing days, when the city’s de facto segregated schools became a national story. The reaction to him for years was that he was too bitter and needed to accept the African American situation better.

In retrospect, he was liberated by his refusal to play along. After teammates Satch Sanders and Sam Jones were refused service at a coffee shop in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1961, Russell joined them in a boycott of a game against the St. Louis Hawks.

“We’ve got to show our disapproval of his kind of treatment or else the status quo will prevail,” Russell said afterwards. “We have the same rights and privileges as anyone else and deserve to be treated accordingly. I hope we never have to go through this abuse again… But if it happens, we won’t hesitate to take the same action again.”

In 1964 Ruseell was again in the middle of a historic act of protest as he led a faction of players at the 1964 All-Star game that threatened to not play unless NBA owners formally recognized the players’ union and granted them a pension plan. The strike ultimately worked as then-commisioner Walter Kennedy acceded to the players’ demands. Russell broke further ground two years later, succeeding his friend and coach Red Auerbach to become the NBA’s first Black head coach while still playing center for Boston.

His outspokenness and advocacy extended to his relationship with the Basketball Hall of Fame. Inducted in 1975, Russell refused to attend the ceremony or accept the honor because he believed other African Americans deserved the accolade first and the selection process had been tainted with racism. He accepted his ring in 2019. This came after former NBA forward Chuck Cooper, who became the first African American to play an NBA game in 1950, was inducted into the 2019 Hall of Fame class.

While still a player, Russell participated in the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, as well as being seated in the front row for Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream speech” and in 1967 the Muhammad Ali summit after tensions rose due to Ali’s refusal to serve in the army during the Vietnam war.

Bill Russell’s accomplishments in and out of the sport are weighty. Decades after his defense of players’ rights and racial justice, the NBA players’ union has become arguably the most powerful in major sports. The NBA has been rightly praised for its record on racial diversity in coaching and leadership. All of these developments can be traced back to Russell’s outsized influence off the court in addition to his accolades on it.

Micheal Jordan described Russell as “a pioneer - as a player, as a champion, as the NBA’s first Black head coach and as an activist. He paved the way and set an example for every Black player who came into the league after him, including me. The world has lost a legend. My condolences to his family and may he rest in peace.”

The world may have lost a legend but his impact and influence on American culture cannot be understated. To appreciate Bill Russell as the consummate winner and trailblazer will be our challenge as the history of sport evolves and builds upon the architects of our sporting past.